Share

“What If Indians Invented Photography?” An Exploration of Identity and Photographic Practices by Indigenous Photographer Will Wilson

Today, on The International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples, we’re sharing the work of the talented Indigenous photographers in the indus...

Today, on The International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples, we’re sharing the work of the talented Indigenous photographers in the industry.

Last week, in anticipation for this celebration, I reached out to Will Wilson, a Diné photographer and trans-customary artist whose work centers around continuity and flow within Indigenous cultural practice. (Note: “Diné” refers to citizens of the Navajo Nation.)

Quite the accomplished artist, Will studied photography, sculpture, and art history at the University of New Mexico (MFA, Photography, 2002) and Oberlin College (BA, Studio Art and Art History, 1993). In 2007, he won the Native American Fine Art Fellowship from the Eiteljorg Museum, in 2010 the Joan Mitchell Foundation Award for Sculpture, and in 2016 the Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grant for Photography. He’s also held visiting professorships at the Institute of American Indian Arts (1999-2000), Oberlin College (2000-01), and the University of Arizona (2006-08). In 2017, Will received the NM Governor’s Award for Excellence in the Arts. His work is exhibited and collected nationally and internationally.

Currently co-curating the first major American museum survey of contemporary Indigenous photography for the Amon Carter Museum (opening in 2022), I got in touch to learn more about how he’s reclaiming Indigenous identity through his long term tintype photo project, The Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange (CIPX), the settlers’ gaze and what’s in store for him this year and beyond.

The following interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length. Cover images by Will Wilson.

As a Diné artist, you’ve spoken widely about how Indigenous people have been depicted in photography. How has the settlers’ gaze, like what we see in Edward S. Curtis’ The North American Indian, affected the way we understand Native North America?

A couple well-trodden frameworks are the notions of the “ethnographic present” and the “salvage paradigm.” Basically, these rhetorical devices of the White settler imaginary (gotta love the jargon!) propose that contemporary peoples/cultures somehow exist in a parallel, anachronistic universe/reality and that they need to be documented before they vanish.

This delimits culture by setting up a set of rules for what is “authentic,” or real and what has been lost/ruined through assimilation and acculturation. Where have all the real Indians gone?

Something else that this “settler gaze” enacts is a kind of imperialist nostalgia where colonisers and other agents of forced change romanticise a previous way of life that they have actively been involved in changing.

When Curtis landed in Oklahoma in the summer of 1927, near the end of his The North American Indian project, he lamented just this notion. Summers are rough in OK (very hot and humid), and a lot of the Indians were vacationing in Colorado. In 1927, there were many wealthy Indigenous people from OK, because of their oil interests.

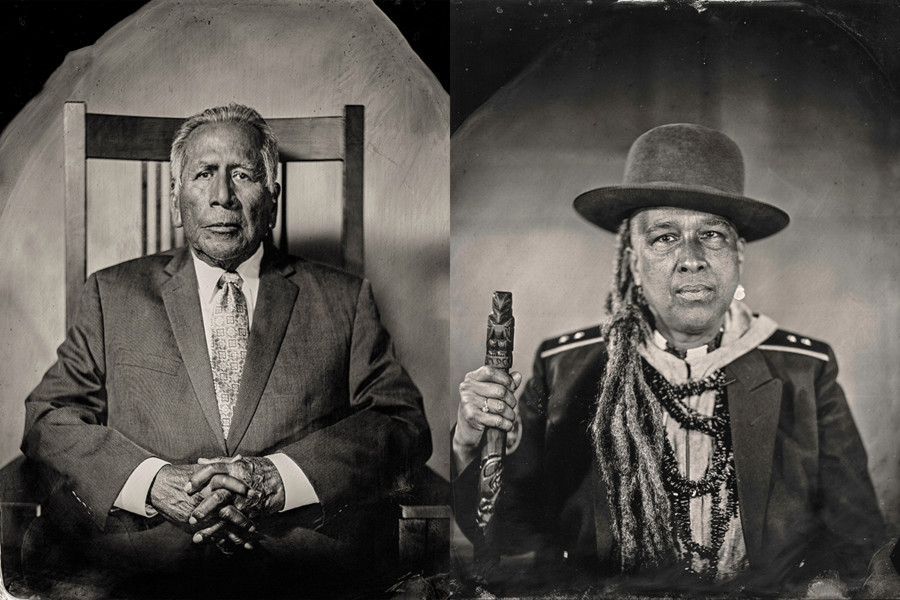

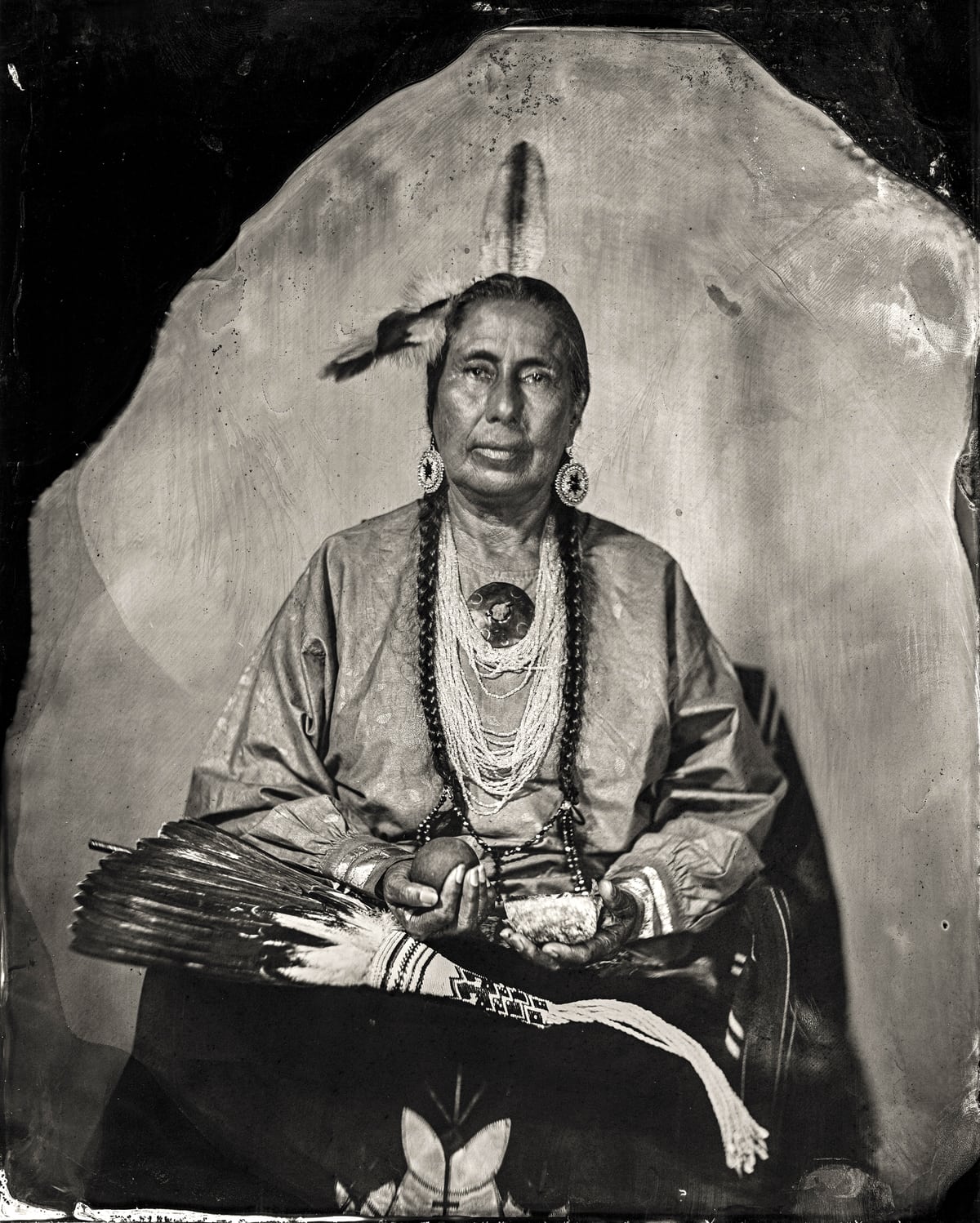

On the other hand, when we are presented with the visual evidence of cultural transformation and modernity there is this wonderful disruption of expectations that is a powerful tool to play with as an Indigenous artist/photographer. Playing with expectations, contradiction and ambivalence is really at the heart of the Talking Tintypes project. It’s also about sharing an amazing process and creating time and space for conversations about photography.

Speaking of tintypes, yours just completely stopped me in my tracks – the expressions you’re able to record, the variety in the items of significance your sitters brought along, the intergenerational bond in your family portraits. Why do you love tintypes so much? When did you learn how to make tintypes?

The wet plate process is sublime in the way that it chemically inscribes light’s trace of the world. This kind of photography is magical and in today’s digital age it really is a kind of alchemy. Don’t get me wrong, I appreciate digital tech and I am enamored with drones and Augmented Reality at the moment. But my first love is analog photography and the wet plate process is very analog.

In 2012, I had the opportunity to kick off my CIPX project and I knew I wanted to use wet plate to make unique photographic objects (tintypes), gifting them to my sitters in a gesture of reciprocity. The CIPX project’s tagline might be, “What if Indian’s invented Photography.”

Coincidentally, my Santa Fe, NM studio was around the corner from Bostick and Sullivan, one of the premier historic photo process chemistry producers in the U.S.! Dana Sullivan generously stepped me through the process, hooked me up with the tools and some chemistry, and the rest is history. Bostick and Sullivan is an incredible resource run by an amazing crew, I can’t credit them enough for my knowledge of this historic, analog process.

Wet Plate evokes history and it does this in a visual, extra-linguistic manner that gets to my fascination with photography as a medium and art form. For example, my interest, to a large degree, is because it was the process being used when the first photos of Diné (citizens of the Navajo Nation) were created.

In your description of CIPX you say you have a desire to indigenize the photographic exchange. What does that look like for you?

It’s really about applying an ethics-based aesthetic to photography and particularly portraiture. It’s why I give my sitters the original photographic object in exchange for a scan.

I also have a non-exclusive photo rights release that allows the sitter to use their image however they choose. Also, if people ask me not to use the photos I respect that. Really, it’s about respect and understanding that a portrait can be a powerful thing.

There is this Hollywood adage about Indians fearing photography because of its capacity to steal the soul. I think that Indigenous people coming from oral traditions have a very nuanced understanding of the power and capacity of descriptive representation and therefore approach the medium with a healthy degree of suspicion and skepticism. So, it’s from this foundation that the project is “Indigenizing” the photographic exchange.

I was so delighted to see that you’ve been a PhotoShelter member for over a decade! Can you share a bit about how you use your PhotoShelter account?

I really need to sit down and update/explore and take advantage of all that PS offers. Like so many Gen Xer’s—my kids constantly mislabel me as a “Boomer”—I set the site up and let it do its job. It’s really hard managing everything as a creative and a full-time educator, so setting it and forgetting it has been my MO. Thankfully, PS made this super easy, intuitive and beautiful on all platforms – computer, tablet, phone. I realize there is so much more functionally that I have not taken advantage of and I really need to be more disciplined about using it!

What’s in store for you for the remainder of 2021 and beyond? Have any exhibits planned?

In 2021, I had a couple exhibitions, one with a former student, now collaborator, Kali Spitzer, at the Hood Museum at Dartmouth College. I also had a show of my Connecting the Dots/AIR series at UT Austin’s Visual Arts Center and am exhibiting and producing CIPX at Denison University this fall.

I am also planning a lot for 2022: co-curating the first exhibition focused on Contemporary Indigenous Photography at a major US museum for the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Oct. 2022 and an exhibition at SECCA, the SouthEastern Center for Contemporary Art.

Anything you’d like to add that I might have missed?

I’d love for people to check out the Connecting the Dots project:

Connecting the Dots for a Just Transition intends to shape a platform for voices of resilience, Indigenous knowledge and restorative systems of remediation while bearing witness to a history of environmental damage and communal loss on the Navajo Nation. This innovative plan is based on a photographic survey of the over 500 Abandoned Uranium Mines (AUMs) located on the Navajo Nation. These AUMs are physical manifestations of a complex and traumatic history that has poisoned the land and endangered a people. This investigation will focus on the toxic legacy of uranium extraction and processing on Dinétah that continues to threaten the health of our people and land. Bearing witness to these sites, and the front-line communities affected by them, the project will serve as a catalyst for designing innovative solutions that refocus our understanding of what remediation can be. The project intends to develop new strategies of remediation that center Diné ways of knowing as it weaves together the interdisciplinary expertise required to address this pressing concern.

At the moment the gallery is set up for grant reviews to see examples of some of the working ideas for the project: the drone-based aerial survey of abandoned uranium sites on the Navajo Nation and prospective TT portraiture/stories of frontline community members affected by the issue of radioactive environmental contamination.