Share

James Beard Award-Winning Photographer Cooks Up a Tasty Newsletter

New Yorker Gary He (@garyhe) has been through a lot. While a student at Stuyvesant High School, he lived through the trauma of September 11 a block...

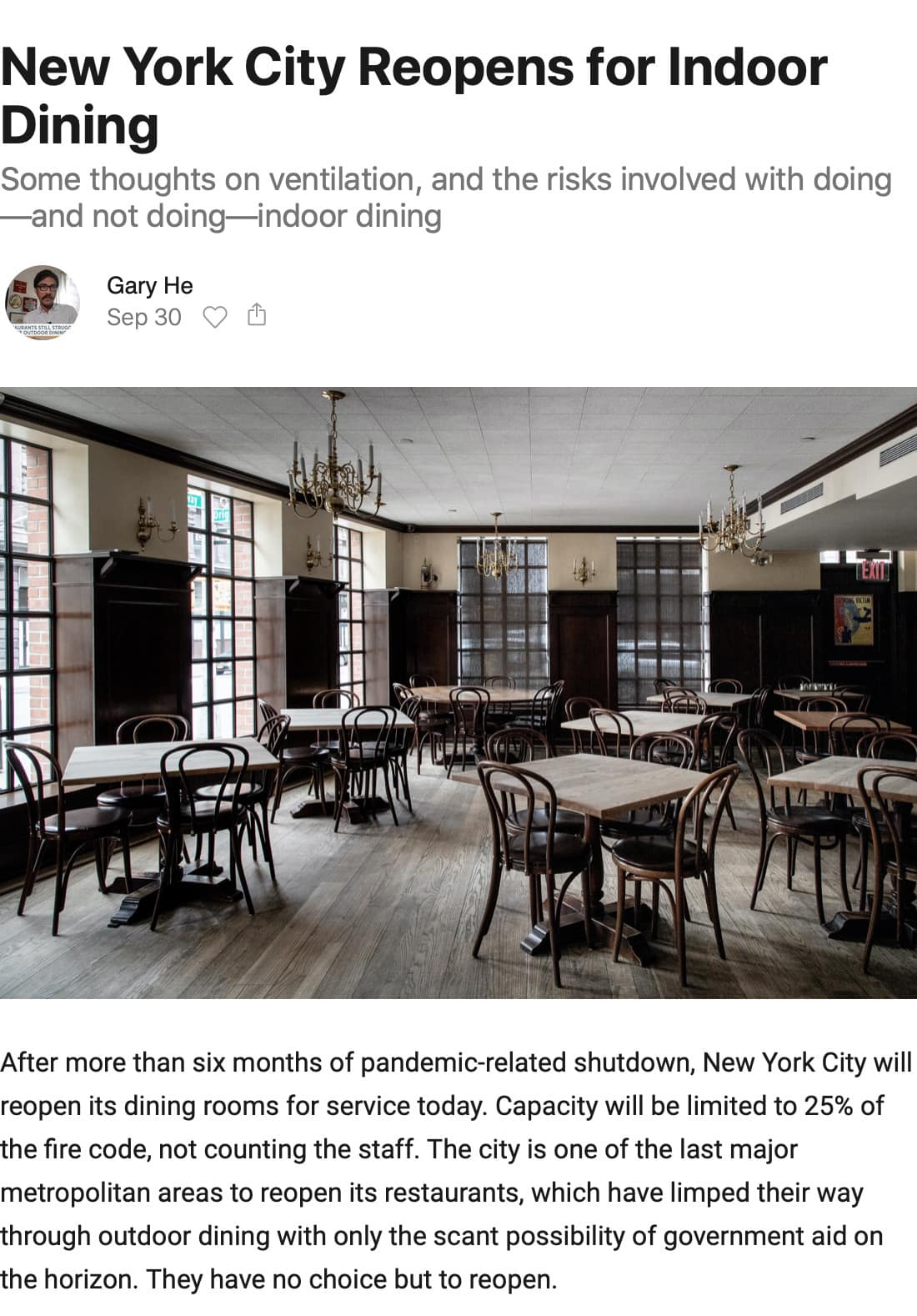

New Yorker Gary He (@garyhe) has been through a lot. While a student at Stuyvesant High School, he lived through the trauma of September 11 a block from Ground Zero. After graduating from NYU with a degree in journalism, he entered the arduous world of freelance photography covering news, events, politics, and more – while starting a few photo adjacent start-ups on the side. And now, he’s trying to figure out how to make a living as a photographer in pandemic.

Foodies are probably familiar with He’s work on Eater. And even non-foodies have probably come across his James Beard award-winning coverage of presidential hopefuls eating (Pete Buttigieg is a particularly enthusiastic eater).

COVID-19 has upended the photography profession, and forced many photographers to reconsider how to make up for lost income. Always the entrepreneur, he followed in the footsteps of many journalists using Substack to create a subscription-based weekly newsletter called Astrolabe, which focuses on the NYC high end dining scene. Unlike many journalists, He’s stellar photography combined with his narrow geographical focus differentiates his product from almost any other. And did I mention that his newsletter perfectly aligns with my interests? Yes, I’m a paying subscriber.

Direct-to-consumer patronization has been very popular with musicians and gamers for years on platforms like Patreon, but there aren’t many examples of photographers successfully building subscriber bases. With that in mind, I reached out to He via email.

***

With your recent James Beard award for Innovative Storytelling, is it accurate to say that you’ve become known as a food photographer/journalist in the past few years? How and why did that happen?

We’ve known each other for a long time Allen, and I think we can both agree that I can’t seem to stick to just one project at a time. Coverage of food and restaurants is something that I’ve been doing since 2016 as a way to avoid “doomscrolling the news,” as Karen Ho puts it. It has achieved this goal about half of the time. The James Beard Foundation has been gracious enough to recognize my work twice, this time for coverage of how candidates eat on the campaign trail.

Photographers are often pigeonholed as single-skill practitioners, but you’ve been writing most of your stories for Eater along with making pictures. How did you cultivate your writing skills, and was it a hard sell for your editors to allow you to write and photograph?

I went to school for journalism but the process is quite intuitive. When people first learn how to photograph, they try to find work that they really like and then learn about the settings and lenses involved in making those images. The same applies to writing: just read a lot of stuff that you want your work to look like, and then reverse engineer the puzzle pieces that were required to put it together: the interviews, the on the ground details, all that good stuff. Read, read, read.

What you say is true: one of the most frustrating things about trying to be both a writer and a photographer is that editors will often try to pigeonhole you into one thing. But I also learned that even the best writers (especially the best writers!) often require a ton of editing and cleaning up. So because I learned how to write by digesting tons of already edited news and feature articles, I file pretty clean copy. It’s not artfully structured or particularly high level, but it’s clean, which makes less work for the editors to be able to push back on.

You recently launched a subscription-based, NYC food scene newsletter called Astrolabe using Substack as your publishing platform. Can you talk about the genesis of the idea? If COVID-19 never happened, would Astrolabe exist?

There are a lot of reasons for why Astrolabe got started, but the most honest one is probably that my corporate photography business got nuked at the start of COVID-19 and has been slow to recover, which is probably relatable for a lot of people reading your site.

At the same time, I developed a niche as I continued to file stories to Eater. Food journalism typically involves happy stories about tasty things, but telling the story about food and restaurants in New York this year has required a lot of nitty gritty, risk, and quite frankly willingness to take on other people’s trauma. Media outlets aren’t exactly doing great, and Eater just didn’t have the capacity to take on my entire output. So I forked some of it over to a project that I could run myself and continue to play my role as that niche storyteller for New York.

You’ve pursued a number of entrepreneurial ventures, so you’re well acquainted with the difficulties of building a business. What are the economics and time commitment for this type of project? If you don’t reach a target number of paid subscribers, do you fold the operation?

It’s important to think about these things before starting any project! There is the very real possibility that I end up working on this for not that much money, but a number of things have been set up favorably: The obligation to subscribers is quite low, just one e-mail a week, and it could easily be written in a digest format. Right now I am cranking out two or three feature-length things a week just to grease the wheels, but I can at any point just snap my fingers and make the overhead very low. Plus, reporting and writing about food in New York is something that aligns with my interests, so it’s not like it would be overly burdensome to continue alongside other things. Finally, there’s no one really doing similar reporting, so there’s definitely this desire to continue telling these stories and fill this gap in coverage.

You picked a niche (Michelin restaurants) in a relatively small geographic region (NYC). If other photographers were interested in pursuing similar projects, do you think a hyperfocus is necessary to break through the noise?

I think it’s more accurate to say that I started with Michelin restaurants and NYC, and it’s safe to say that I will eventually use the newsletter to cover much more than that. Going back to the topic of preparation for any project: what gets the most hits on food/restaurant websites? Michelin content. What are my areas of expertise? New York City restaurants. So I started from there. I think photographers that want to start their own projects but don’t have a large baked-in following that they can port over from another platform would be wise to stick to their area of expertise. That is, after all, why anyone would want to pay them money.

Is word-of-mouth the marketing plan to reach your first 1000 customers?

No paid media for now, but there are the usual suspects like being annoying on social media platforms and expanding my media outreach, including interviews with outlets that may potentially have subscribers. Hey did I mention that you can subscribe to my newsletter for free at http://astrolabe.substack.com?

Much has been written about the “death” of New York City in light of COVID, and while I don’t agree with the pessimistic prognosticators, this does feel qualitatively different from 9/11 and the various financial meltdowns that I’ve lived through. What do you think the NY restaurant scene looks like in 2022?

Some restaurants just aren’t going to survive the slow return of midtown workers. The ones that relied on big catering or buyouts to survive are probably dead. But the neighborhood ones that can re-negotiate their lease because everyone is part of a community? And although they weren’t making that much money to begin with, their costs are just a percentage of revenue and they’ve been able to adjust how they do business? Those will hang on and be here in 2022. Restaurants that have opened during the pandemic have a lot of those qualities, including leaner staffing, which means there’s more self-service.

People have been talking about the city’s decline for decades, and even when the city was in its darkest days, some of the city’s now foundational restaurants like Le Bernardin, Daniel, and Union Square Cafe, were first opened. Are we backsliding that far? I don’t see it. A lot more money is invested here now than in the 1970s, and more of it is likely to stay. Even now, you can barely get a reservation at the city’s top restaurants, where a meal will run you a couple hundred bucks. Sorry to the haters, but New York City isn’t going anywhere.