Share

Navigating Copyright Law and Fair Use for Photographers

Understanding the ins and outs of copyright is an asset to your business. As the world of professional photography continues to move online, it wi...

Understanding the ins and outs of copyright is an asset to your business. As the world of professional photography continues to move online, it will become increasingly important to understand what rights your creations are granted and what options you have in defending those rights.

We recently put together The Photographer’s Guide to Copyright in partnership with ASMP to help photographers navigate the world of copyright law. One topic covered in this guide is Fair use, and the following article is written by Eugene H. Mopsik, ASMP Executive Director and Victor S. Perlman, ASMP General Counsel and Managing Director.

Defining Fair use

Fair use is one of the grayest of gray areas, and possibly the most misunderstood, in copyright law. It’s not a right, as commonly believed, but a defense that is raised when there is an infringement claim. Ultimately, whether a particular unauthorized use of copyrighted materials qualifies as fair use can be determined only by the courts – everything else is just guesswork and opinion.

Sometimes, though, even the court decisions seem to come down to guesswork and opinion. There’s probably no better example than Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart’s famous quote – when expressing frustration trying to define obscenity he said, “I know it when I see it.”

A little background

Fair use exists in the U.S. because of §107 of the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976. In the introductory section of the Act are some examples of the types of purposes that the fair use provision is intended to support: “…criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, or research…” This list is not exclusive or comprehensive, so uses for other purposes may qualify for fair use. We know this because that list is preceded by the word “including.” Conversely, just because a use is for one of the listed purposes does not mean that it is automatically fair use.

For example, if uses for teaching purposes were automatically considered fair uses, there would be no textbook publishers left in business, since most of the buyers of textbooks would simply make unauthorized copies of desired books rather than buying copies, and the infringers would be protected by fair use.

The statute goes on to make it clear that each claim of fair use has to be determined on a case-by-case basis (“…determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use…”). This means that, where fair use is concerned, there are no absolutes or black and white rules. If you ever hear a statement to the effect that “ABC is always fair use” or “XYZ is never fair use,” you can be pretty certain that the statement is not true or accurate.

What is considered Fair use?

The language of §107 then goes on to provide some guidance in how to determine whether a particular use is a fair use by providing a list of four factors to take into account when analyzing the situation:

- the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

- the nature of the copyrighted work;

- the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

- the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

Again, the statute uses the word “including” to show that the list is not comprehensive or exclusive, so other factors may be considered. Similarly, no single factor is determinative, and all must be considered.

The courts have varied from time to time in their opinions as to which of the four factors is the most important. Since the statute requires a consideration and discussion of each of the four factors, that is the approach that we are taking here:

1. The purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes

The goal of the first factor is to consider the public benefit versus the private benefit of the use. Under the first factor, a number of myths have evolved, including:

Myth #1: Absolute statements (referred to above), such as “no commercial use can ever be fair use;” “nonprofit educational uses are always fair uses,” etc. are true.

Myth #2: Originating from a 1990 Harvard Law Review article that was cited with approval by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1994 where the concept of a “transformative” use was a fair use.

Unfortunately, over the years, the concept of what “transformative” really means has become misunderstood and misinterpreted, especially by the public, so that many people believe incorrectly that any change made to a copyrighted work, no matter how slight or insignificant, is enough to qualify as a fair use.

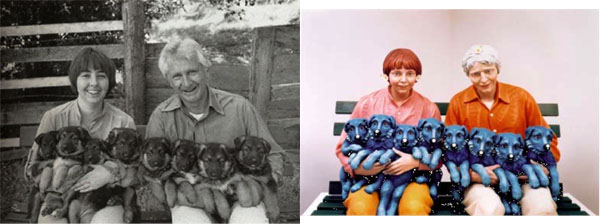

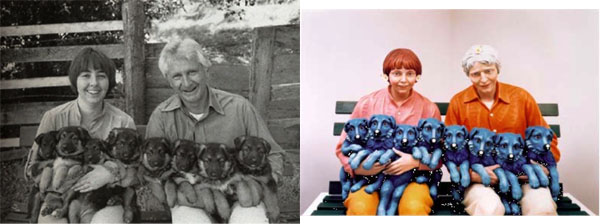

Case study: A great way to judge the impact of the “transformative” concept is to compare the different results in two cases claiming infringement of photographs by sculptor Jeff Koons. In Rogers v. Koons, which was decided by the Supreme Court in 1994, a sculpture closely resembling, and based on, a photograph of a couple holding a group of puppies was found to be an infringement, not a fair use.

2. The nature of the copyrighted work

The second factor is important because one cannot own a copyright for an idea or concept, only for one’s personal expression of that idea or concept. Because of this, works that are fictional or highly creative tend to be heavily protected by copyright, while factual and scientific works tend to have very thin protection.

In other words, the second factor is more likely to be found in favor of fair use where a work is factual or scientific

and less likely where it is fictional.

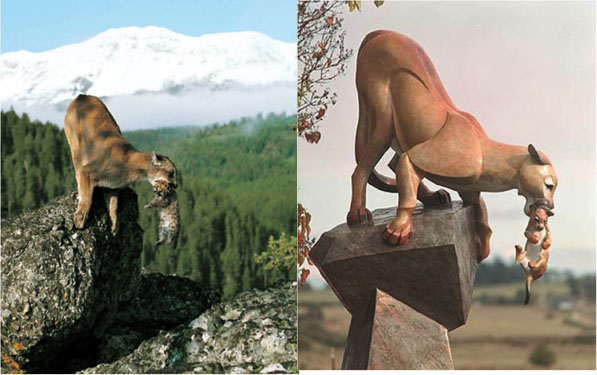

Case study: A good example of this is the decision in Dyer v. Napier, where a photographer set up a scene in which a mountain lion cub was placed on a dangerous outcropping of rock and the mother lion was then released to retrieve the cub and move him to safety. This photograph was used as the basis for a very similar statue, which was found to be a fair use.

3. The amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole

The third factor takes into account the quantity and quality of the original work used in the unauthorized one. As one would logically expect, generally, the more of a work that is used without authorization, the less likely the use is to be found fair under this factor.

Similarly, the more significant the portion of the work that is used is, the less likely the use is to be found to be a fair use under the third factor. Once again, though, remember that no single factor will determine a finding for or against fair use.

4. The effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work

The fourth factor takes into account the potential financial impact of the unauthorized use on the copyright owner. This factor is one of the reasons why almost every infringer tries to claim that the unauthorized use benefited the copyright owner in some way, often by way of “free advertising.”

An important thing to remember is that the loss of a licensing fee that the copyright owner would have charged the unauthorized user who is claiming fair use does not count. Otherwise, the fourth factor would have to be found in favor of the copyright owner in every case.

Remember, there are no absolute rules regarding fair use. When in doubt (which is just about every situation involving fair use), talk to a competent copyright lawyer.

Learn more

The Photographer’s Guide to Copyright will help you break down copyright law, understand your rights as a photographer, and take steps to protect your work from infringement. Get tips to keep your work safe, plus read in-depth interviews from photographers and experts from ASMP.